Lolita - Young Matrix, Unknown Heart

/“Please, reader: no matter your exasperation with the tenderhearted, morbidly sensitive, infinitely circumspect hero of my book, do not skip these essential pages! Imagine me; I shall not exist if you do not imagine me; try to discern the doe in me, trembling in the forest of my own iniquity; let's even smile a little. After all, there is no harm in smiling...”

Vladamir Nabokov- Lolita

This is a confession: I am exactly the kind of person who Humbert Humbert wants to reach in his self-described confession. Intoxicated by the mere sound and visceral feeling of words on the palette, I willingly overlook the crimes of Nabokov’s narrator and am not, as ethicists argue I should be, entirely disgusted with him. Instead, I marvel at him. I inhale the delectable images, the depth of his passions, and find myself drawn in.

I find myself admiring a pederast, because he loves beautifully.

When Peter Steeves, Professor of Philosophy at DePaul, and President of Theatre Y’s board of directors, asked us if would perform a twenty five minute rendering of Lolita for his “Making the Novel Novel” series, I jumped at the chance. The name of the book inspires such division that, despite my limited knowledge of the novel, it was exciting to be part of the discourse.

I also fully understood Peter’s reasoning behind his presentation of the book. That H.H.’s real crime is not his rape and imprisonment of a 12 year old girl, but his misogyny. Replaced with a woman of legal age, his crimes would be no less appalling, and in fact reveal behavior that is fairly common. He hurts, and then attempts to make himself more lovable by showing how hurt he is by his own actions. How regretful he is. This is the language of a circular, abusive relationship, of codependency that sustains itself not in spite of, but because of abuse. Remorse covers up, and allows the pattern to continue until it ends, often brutally.

Nabokov also uses the language of traditional, romantic discourse, whose passion often covers up the questionable behavior of its writer. By transferring this language to the love of a girl under the age limits of what is societally acceptable, he stoops under our defenses. He problematizes this discourse, but also brings H.H’s actions down to a level where they are more acceptable, because we are allowed to feel with him.

However, this was obviously not Nabokov’s intent. In fact, when he was alive he made it very clear that he balked against any piece of literature in which he detected a social or moral lesson. “…Lolita has no moral in tow. For me a work of fiction exists only in so far as it affords me what I shall bluntly call aesthetic bliss, in that sense of being somehow, somewhere, connected with other states of being where art (curiosity, tenderness, kindness, ecstasy) is the norm.”

An author’s intent, as Adorno, among other 20th century philosophers have pointed out, has little to do with the context or content of an artistic work. And yet I think it is important to dwell on his objection. Lolita is one of the most contentious novels of the past century, and it is so because it allows so many different interpretations. It is about pedophilia, it is about poetry, it is about normative sexual relationships, anarchy, and even about America. None of these are mutually exclusive. To argue for an interpretation can clarify certain aspects of the text. But to argue that there is a single interpretation does violence to the raw text. H.H.’s self-condemnation gives Lolita a moral slant. But the pathology of the meta-novel, its obvious fictionality, obscures it. Nabokov distances our moral condemnation through his mastery of the poetic form. Thus, the novel rests in ambiguity.

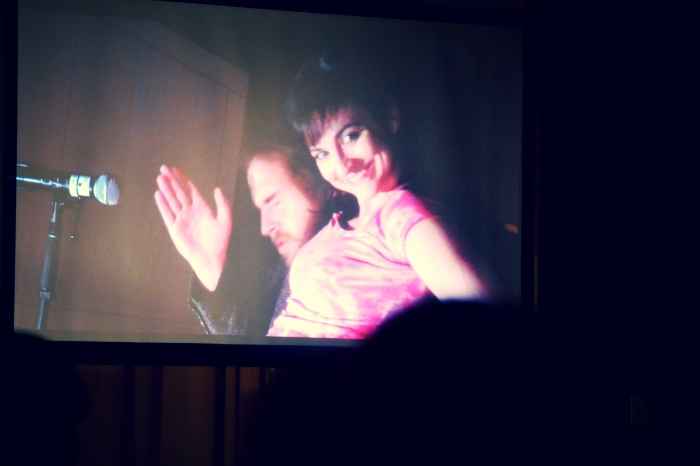

As a theorist, I do have a preferred interpretation of the text. But as an artist, my task as I saw it was to create something that aped the novel, while at the same time bringing something new to the table. Instead of making a piece that favored one particular interpretation, I decided that formal novelty was the best option. Lolita Remixed in the form of a textual collage, sampling significant portions of the novel and of Kubrik’s film adaptation. With the text in hand, Evan (playing H.H.) and Melissa (Playing Lo) have created a performance that is at once utter blasphemy to Nabokov’s technical structure, but simultaneously retains the novel’s emotional heart and poetic imagination. By inverting, scrambling the novel, we hope to do what Humbert Humbert, with his beard and his putrefaction, could not: apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys…