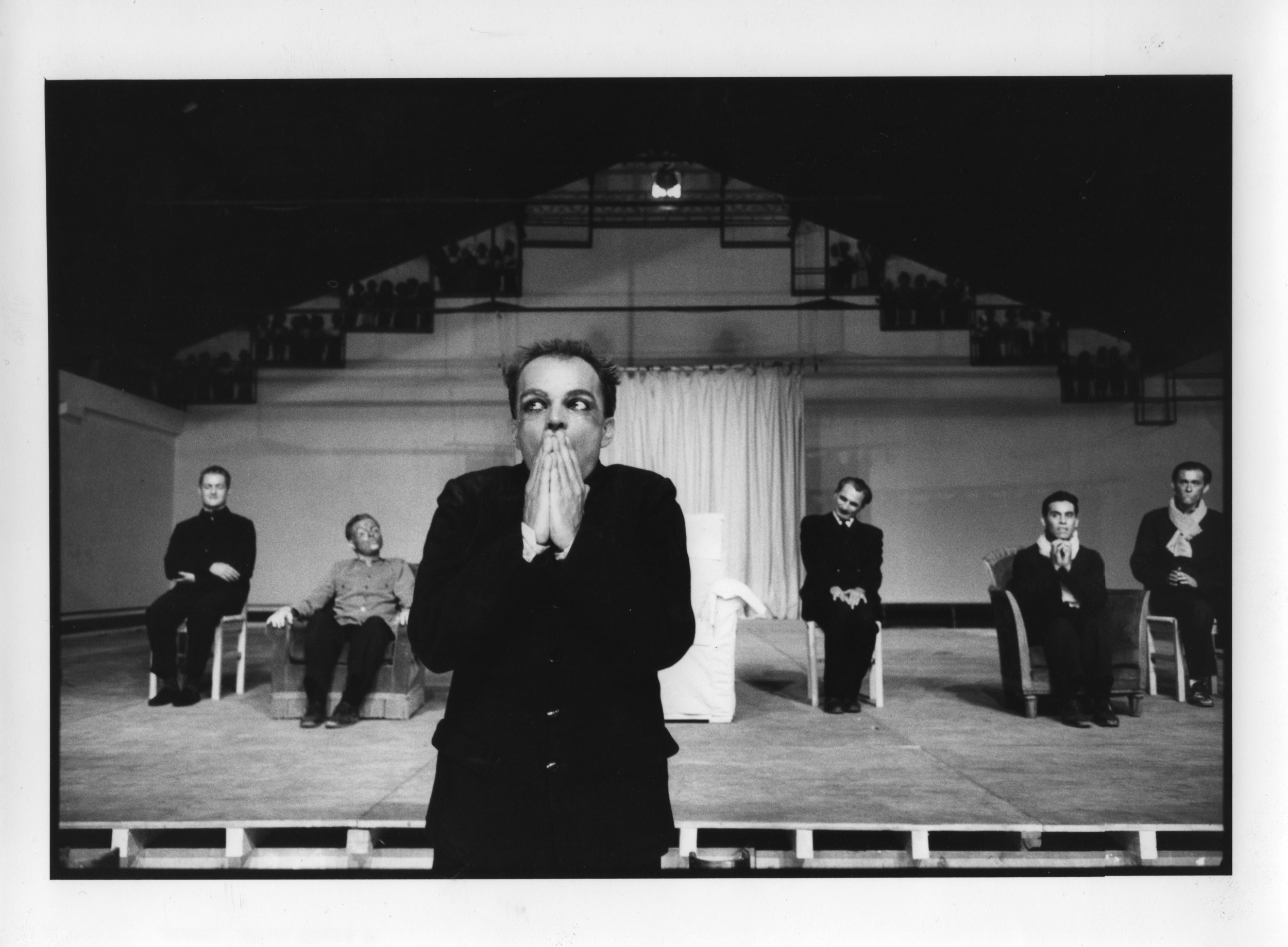

Georges Bigot Workshop

/As recounted by Theatre Y's new Dramaturg Dan Christmann

What is my text?

Make some sort of proposition.

For my text?

Sure, why not propose something, that’s all there is. It’s for the work. It’s the base to begin. You’ll rewrite the whole thing again in fifteen minutes anyway. So make something. Propose it.

Now.

“What do we want to say about this Bigot thing?”

Evan Shrugs. “I don’t know. Its. It’s not even a thing at this point, as far as I know.” He reaches over with his fork and spears a piece of French toast from Melissa’s plate, just as she takes a sliver off of the duck tacos on his. This exchange has been going on for the past fifteen minutes without anyone realizing it, or at least no one is mentioned it, and so it seems like there is some sort of unspoken equilibrium between the two of them that always has to be balanced, scales weighed, justice measured. Evan wipes his mouth on one of the many suit jackets he always wears, and keeps right on going through the food, his hands flowing through the air as if to demonstrate each nonexistent point. “We might be doing Shakespeare, we might be doing something else with him. But anyway, there’s a workshop Melissa has going with Georges at the end of the month or so, so maybe he could come to that?

He glances over at Melissa. Her face lights up. “Oh yes, of course, that’s perfect Buddy!” I like talking with these two, but it’s especially entertaining to watch Melissa’s face when an idea strikes her. You can almost see the process from consideration to unrestrained joy, from zero to fifty, from seed to blossom.

“Sure.” I nod. Probably I am unconsciously pulling at my facial hair. Laconic, as always. Do I have any questions about the workshop? A few. Do I have any thoughts about my role? Maybe. But, because I am a kind, affable soul who tends to acquiesce to everything, all of the answers satisfy me. We go on to talk about other projects, which excite me more at the time. A new Andràs Visky play, an integral role in organizing the company’s season. I do not even know who Georges Bigot is, and the Theatre du Soleil I have heard of maybe once or twice in passing, and, since I do not remember much about them, don’t interest me particularly. If I don’t remember, it must not be interesting, right?

Right.

But I am off of my text.

“Have you any commission from your lord to negotiate with my face?”

No, by the rood, not so. But we will draw the curtain and show you the picture…

Monsieur Bigot, when I first meet him, reminds me of what would happen if Peter Lorre and Sean Connery had a love child who, estranged from his famous fathers, grew up in France, and developed all of the quirks and verbal habits that a Frenchman speaking broken English inevitably develops. He is shorter than I imagined, and balder too. But his face is remarkably plastic, and the wrinkles around his eyes emanate a kind of effortless grace that has characterized his entire acting career. I shove my hands deep into my pockets as we walk from the airport terminal to Melissa’s car, and keep my thoughts to myself. I am a hermetic sphere bobbing through velvet black of the benthic zone.

By and large this characterizes my interaction with Georges, even throughout the workshop. But you can’t remain an impenetrable singularity in work like this, even if it is your job, more than anything, to sit and absorb. Little by little, you participate whether you want to or not, contribute and are permeated. Georges, I think, takes unresponsive introverts like me as a personal challenge.

I could be bounded in a nutshell and call myself the king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.

These dreams begin essentially as ensemble work. There are about twenty five of us in the workshop, though we are never all together at once. This Irks Georges. But nevertheless, he makes us get up and dance. First we do so individually, and then in groups, with a single person as the chorus leader, who the rest follow in movement. But he doesn’t want us to dance, not really. The intent here is to “follow the score, or the text”. You move as the music interpenetrates you. It is a model of how we are to work with Shakespeare’s text, not to plan forward, but to react, along the contours of each line, to take each turn no matter how sharp or unforeseen.

We spend some time on other exercises as well. We group together and improvise soundscapes. We play games to keep us sharp. But soon it devolves into scene work. Georges is unforgiving in the way he side coaches, yelling out directions from the front of the house to move now, find the internal state, make a proposition, and for the love of god, don’t go home! He communicates as best he can, but there are communications issues that even Bob, the dramaturg and temporary translator, can’t get past. There are a specific set of rules that he has to pound into us before a scene will go forward, and he will sometimes stop a scene even before a word has been said if you aren’t following those rules. After the first week, many of us are confused and frustrated. Fewer and fewer of us show up consistently.

But there are moments of brilliance. Breakthroughs occur, and for those of us who are there to catch those sparks, they illuminate a whole depth of technique and experience that we cannot see to the bottom of. A couple of us slip and fall as we struggle toward the bottom. An actor punches the floor and cries while doing a scene from Macbeth. You can tell from his frustration that, like in me, there is something that resists the way Georges works. We want to have a plan. We want to have an idea and be right. Georges couldn’t care less about whether an idea is good or bad, fair foul, or foul fair. Many of us don’t know which way is up because of this. We hover through the fog and filthy air.

As the work progresses, more and more of us are able to find our way in the charnel theatre space. We grow more comfortable with Georges, and each other. But as soon as we reach a plateau, Georges Sweeps the rug from underneath our feet and tells us that we have to go deeper. You give him an inch and he wants a mile. Each scene goes through a hundred different versions of itself. The three witches from Macbeth dance in on the blasted heath to Little Darlin’ by the Diamonds, a do-wop band from the late fifties.

Two weeks into the process, we throw a party at Chuck’s house. Like in the scenes that we are creating, we collaborate to finish off sixteen bottles of wine between the twelve or thirteen that are able to make it. The night is a kaleidoscope of limbs that dance spiderlike across my memory, of profound conversation, and song. We all trudge to rehearsal the next day with the legacy of the sulfates still hammering on our skulls. But we go on.

At the beginning of the process, many of us were intimidated by Georges and by each other. But now we hang to each other like drunk sailors on the risers, watching whoever it is gets to perform that day. Going on becomes an act of being present. If it be not now, tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. If you can free yourself enough to get through a scene without Georges stopping you, you will be rewarded with a small cry of “Yes!” as he leans toward the stage. He reminds me of man people in the evangelical tradition, who vocalize their assent during prayer. But to him, I think, Theatre is a sort of prayer. It is good that we are working, at least for now, in an old worship area in the back of St. Luke’s, where you can see the arched windows and a cross or two even underneath the black paint.

Georges decides, on the last day, that when he returns from France in May, we will begin rehearsal on Macbeth. But even before then, he instructs us to rehearse, continue working together so that we can all reach by that time the place that only a few of us have been able to get to. Because, in the end, this workshop has to go beyond itself, and is designed to go even beyond this show. From where I stand, it means the creation of a new, or at least more collective version of Theatre Y. It means, even with the loss of the space at St. Luke’s, a new jolt of energy for us. The way we’ve worked, and the connections that we’ve made, should hold, and give us the ability to go beyond where we’ve been before. I’ve heard Melissa call it a new chapter, but I think that’s true in ways that even she couldn’t imagine. It’s the gift that Georges leaves with us.

Yes?

Yes. Well, what do you think?

It was not so bad. But Dan, You must stand straight when you walk. And do not make your feet all Charlie Chaplin.

But I am not shaped for such sportive tricks, nor made to court an amorous looking glass; I that am rudely stamped and want loves majesty to strut before a wonton ambling nymph-!

Ok, is very good, but you are looking always at the ground, so I do not receive this. Try again. From the beginning, ok?

Ok.